Clinical Exchange in Japan

Welcome to Japan and Nagoya University school of Medicine!

Experience Report

Frederick Yeo from University of Adelaide, Australia

Period:2015/5/25 – 6/20

Department: Paediatrics (Haematology & Oncology, Neurology, NICU)

I commenced my elective at Nagoya University with an open mind, not really knowing what to expect. Having read-up a little about the Paediatrics department in Nagoya University just the night before flying off, I realised that they were pretty big on Haematological oncology and Neurology. Little did I realise exactly how big.

Perhaps it was partially due to the fact that haematology-oncology has always been taught as a sort of sub-speciality and hence not heavily emphasised, perhaps it was because Nagoya University as it turns out happens to be the number one stem-cell transplant centre in the whole of Japan, I was soon overwhelmed. Acronyms and rare syndromes that I had never come across in my five and a half years in medical school soon became part of my every day talk with the Japanese Haematologists. I acquired a wealth of knowledge from various sources – textbooks loaned to me, the patients themselves, google, the Japanese medical students and of course, the consultants who gave me heaps of one-on-one tutorials. Just to list a few of the topics covered for my own memory’s sake: Juvennile Myelomonocytic Leukemia (JMML), Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD), Haemophagocytic Lymphohistocytosis (HLH), Langerhans cell histocytosis (LCH), Transient abnormal Meylopoeisis (TAM) seen in T21 which could progress to Acute Megalokaryocytic Leukemia (AMKL) or AML-M7 and who could forget the look on the consultants face when I told him I was unfamiliar with the French-American-British (FAB) classification of AML. “Even the Japanese medical students who I don’t think know a lot, know this” he said jokingly before proceeding to teach me and buy me lunch at the restaurant on the top floor of the hospital overlooking the city.

The hospitality shown by the Japanese people is in a word, unmatched. The entire culture is seemingly centred round courtesy and respect. Even the most senior professors with undoubtedly extensive resumes and volumes of medical research to their names treat their colleagues with respect, starting from their registrars right down to the nurses and medical students. In Japan, everybody seems to bow to everyone else, they do not push and shove, their language structure is polite, and the importance of being punctual for meetings cannot be over-emphasized. Their trains run like clockwork, the commuters run for the trains for fear of being late. Even that old grandpa with the walking stick picked up his stick and ran for the train. What touched me the most however, was how on our first day, the professor from the international students’ office was right there standing by the road, waiting for our arrival, waiting to receive us. He was not sitting in the comfort of his office, he was certainly not late. He being a professor, standing out there on the side of the road waiting to welcome us students just immediately instilled in me a sense of utmost respect and admiration.

My time with the other 2 departments was relatively shorter than that spent in Haem-Onc. Nonetheless, I still learnt a lot. In particular, the use of exogenous Adrenocorticotropin Hormone (ACTH) for the treatment of infantile spasms instead of the conventional use of corticosteroids. The consultant explained to me how it has been shown that ACTH exerts a membrane-stabilising effect independent of the corticosteroid pathway. Interestingly however, outside of Japan, the more conventional management approach is preferred. I was also very impressed when the consultant shared with me how currently genetically engineered CAR-T cells are being created as a form of chemotherapy which would specifically target and destroy malignant cells in leukaemia without exerting any effect on normal healthy cells. This research once brought into active clinical practice would be revolutionary. I was even more excited when one morning I was told to get changed into scrubs and follow the registrar to the operating theatre for I was about to harvest some bone marrow for a bone marrow transfusion later that day. I tried to contain my excitement and enthusiasm as I plunged the drill into the patient’s iliac crest, removed the transducer and aspirated copious amounts of glistening red and yellow marrow. That day I felt like a king.

If I thought things could not get any better, I was wrong. A musical concert put together by the long-stay paediatric patients really made my day. Kids as young as 5 years old, smashing away on the big bass drum about 3 times his size in perfect rhythm and synchrony to the rest of the orchestra filled the ward with joyous harmony. These children practiced for hours per week in the months leading up to their annual hospital summer festival concert. I was told by the play therapist working there that this hospital has a special school for these long-stay children to go to so that they could continue to have as normal an education and social interaction with other children as possible. Something I had never come across before. This is an excellent initiative any paediatric hospital in the world ought to consider. The Nagoya University Choir soon joined in and sang to and then with the children. Paediatric patients really brighten my day.

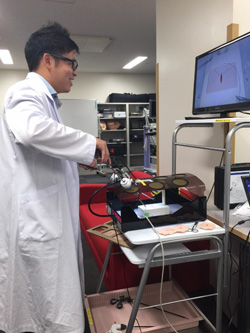

Thanks to my fellow student from Adelaide who was attached to Nagoya University’s Upper Gastrointestinal Surgical unit, I got to play with their laparoscopy simulator lab as well. Compared to laparoscopic suturing, normal suturing was child’s play. The Japanese surgery students made it look so easy but when I tried, to say I failed miserably to close the wound would be an understatement. That day I felt nothing like royalty - an excuse to buy myself an even more extravagant dinner that evening.

Food in Japan was amazing. Following a guide I found online to Nagoya’s best food spots for their specialty foods, we did our best to cover as much ground as we could. Even with 4 weeks in Japan, I dare not say we covered all that there was to in Nagoya. I certainly did not have the pleasure, as did my travel companion, of tasting Nagoya’s speciality coichin chicken served sashimi style. Something I might come back one day to sample, despite the inherent risk of salmonella. Hitsumaboshi (Eel on rice, served in a traditional wooden bowl, eaten 3 ways) was one of my favourites. Kishimen (traditional flat noodles served in a clear broth with vegetables, fish cake and bonito flakes) trailed not too far behind. Tebasaki (peppery-spicy fried chicken wings) was our easy to eat favourite, and who could forget the extremely affordable ramen and sushi from departmental stores or random little restaurants along the streets. Nothing however, beats the day we queued up outside a famous sushi bar in the tsukiji fish market from 530am. The sushi was worth every single minute of sleep lost that morning. I have certainly tasted toro (tuna belly), Uni (sea urchin) and akagai (ark clam) before, but after eating what I thought I was familiar with, served up by this master-chef, I humbly acknowledge my ignorance. Sometimes I believe I can still taste that creamy buttery goodness of fresh Uni on my palate.

All in all, I would definitely recommend Nagoya University as a medical elective destination, not just because of the sheer amount of medical knowledge one would stand to gain from the ever-so accommodating teaching staff there, but also for the overall experience of unadulterated Japanese culture, food and way of living.

Click here to read other stories

Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine